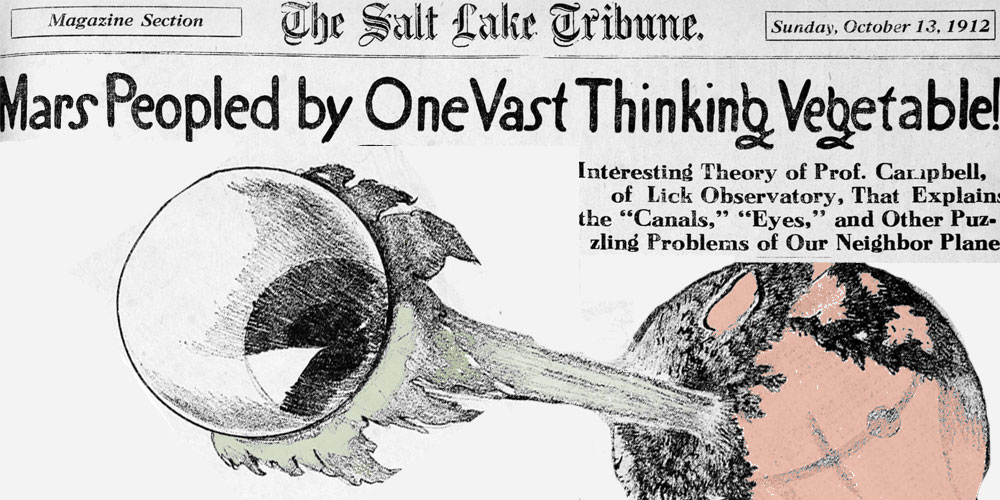

“Mars Peopled by One Vast Thinking Vegetable!” proclaimed a 1912 headline in The Salt Lake Tribune. Citing a professor at the Lick Observatory, the newspaper explained the red planet was overrun by large plants capable of independent thought, each with a single human-like eye growing from its stalk; this was depicted in a prominent accompanying illustration.

In 1912, a story about alien vegetables wouldn’t have been particularly unusual for The Salt Lake Tribune. But today, it’s a Pulitzer-winning independent newspaper carrying the motto “Truth. Empowerment. Community.”

The idea of what the news media is, and does, is vastly different than even a century ago. But while our contemporary press tends to be lighter on reports on sentient Martian greenery, some tropes and tendencies from those early days do stubbornly persist, e.g.,

A Brief History of Nobody Wants to Work Anymore

🧵

— Paul Fairie (@paulisci) July 19, 2022

On this week’s CANADALAND, reporter Cherise Seucharan explores how the media has evolved over the past 100 years, as well as the ways it hasn’t:

On the show, Cherise speaks to Paul Fairie, a University of Calgary instructor who’s become internet-famous for his trawls through the archives of Newspapers.com (and is compiling a book of his finds), as well as Gene Allen, a Toronto Metropolitan University professor emeritus who’s an expert on the evolution of news. His new book is Mr. Associated Press: Kent Cooper and the Twentieth-Century World of News.

Here are edited excerpts of Allen’s observations from the episode…

…on the hyper-partisanship of Canada’s 19th-century press

“Beginning, really, in the 1810s and 1820s, there were small-scale, mostly political papers that represented either the kind of Tory establishment or, increasingly in Quebec and Ontario, the opposition politicians like William Lyon Mackenzie or his counterparts in Quebec. And so the press in Canada, as in the United States, was very much a kind of a partisan political operation for most of the 19th century. If a candidate of your party gave a speech, it was the most brilliant speech in world history. And if a candidate from the opposition party made a speech — if it was covered at all — it was absolutely a disaster.”

…on why newspapers began to adopt standards of neutrality, objectivity, and accuracy

“Around the end of the 19th century, newspaper publishing began to look for larger audiences and find a different economic model, which was based on advertising. And the whole point of having advertising as your revenue source is that you need to get the largest possible number of readers. News coverage began to become less overtly biased, and news agencies were a big part of that, because they supplied up-to-date news through the telegraph to all kinds of newspapers at once. And it had to be news that could be printed in papers of different political affiliations. So that’s how you get a big audience, which is how you get advertising revenue, which is how you’re then able to produce these big, huge papers of, you know, 80–100 pages, with hundreds of thousands of copies, requiring a very, very big physical plant and a lot of capital investment to put them out. In short, journalism became a very big business.”

…on the persistence of narratives of decline

“A joke I tell myself was that when prehistoric people first gained the power of speech, one turned to the other and said, ‘You know, things ain’t what they used to be.’ I mean, it’s always these narratives of decline. As a historian, this is always something that you have to kind of steel yourself against, because there’s a sense that the past was wonderful in some ways that we have lost — and that we’ve lost it because of technology or we’ve lost it because of moral failing or we’ve lost it for one reason or another. One of the fun things about being a historian is you get to actually look back and say, ‘Well, was it actually all that much better? Was the golden age any more golden?’ Some people in my field say, ‘Boy, the partisan press was great, because they treated people as citizens and they put their political biases out there explicitly, and this turn toward namby-pamby mass-audience stuff was, you know, just based on trying to get ad revenue.’ But if you actually look at that coverage, it’s not very informative. I mean, it’s basically propaganda.”

…on pandering to frightened readers searching for answers

“‘Moral panic’ is the idea that moral failings are the cause of whatever ill you want to mention and that something is causing these moral failings. Like the telephone in the 1890s, that allowed young men to speak to young women unchaperoned and that this was a terrible, terrible thing breaking down all norms of social propriety. There’s a lot of moral panic about technology — not to say that certain technologies don’t have problematic social effects, they do for sure — but there is that sense of moral failing, where moral standards and practices are called into question. And it’s easy to sort of say, ‘Well, if people just weren’t lazy, if they tried harder, we would be okay,’ looking for individual, rather than social, explanations of what’s happening.”

Top image adapted from the top of the magazine section of the October 13, 1912, edition of The Salt Lake Tribune.