For most Canadians, it can be oddly easy to pay little mind to India and its politics, even as the country has recently been serving up the biggest protests in human history. In India’s political imagination, however, Canada occupies an outsized role, portrayed by its far-right government and supportive media as the home and enabler of diasporic radicals upon whom all manner of domestic ills can be blamed. In other words, Canada — and particularly its Sikh population — is a popular bogeyman in a place that, despite authoritarian slippage, remains the largest democracy on Earth.

On this week’s CANADALAND, Jaskaran Singh Sandhu — administration director at the World Sikh Organization of Canada, consultant at Crestview Strategy, and co-founder of Baaz News — talks to host Jesse Brown about the peculiar dynamics that have seen Canadians blamed for fomenting a popular uprising on the other side of the planet.

In preparation for the interview, Canadaland Media’s Arshy Mann wrote up a briefing note for the show’s team, laying out the intertwined histories of India, Canada, and the Sikhs, and how they’ve led to a context in which Canadians have become regular targets of propagandistic disinformation campaigns.

It not only explains the individual components of the story but helpfully ties everything together, and so we’re glad to share a version of it with you.

Sikhi or Sikhism is an Indian religion founded in the 15th century, drawing from both Islam and Hinduism. Over the next two centuries, the Sikhs emerged as a political and military force in the north of the Indian subcontinent. After the fall of the Mughal Empire, an independent Sikh Empire existed for 50 years, before finally being defeated by the British in the mid-19th century.

Over the next 100 years, Sikhs were both the backbone of the British Indian military and at the forefront of resisting British rule. When the subcontinent won independence after World War II, it was partitioned along religious lines, with Muslim-majority areas forming Pakistan and Hindu-majority areas forming India. At the time, many Sikhs were pushing for an independent Sikh state. Instead, the Punjab region was partitioned between Pakistan and India, and the majority of Sikhs living in Pakistani-Punjab fled to the Indian side.

When the Constitution of India came into effect in 1950, Sikhs were again largely disappointed. Many Sikhs had wished for a loose federal structure with autonomy for the states. Instead, the centre retained a great amount of power. Also, the constitution set aside different legal systems for customary issues such as marriage, divorce, and adoption. Separate legal codes were created for Hindus, Muslims, and Christians, but Sikhs were lumped in with the Hindus.

In the 1970s, Sikh opposition to the central government increased, with Sikh leaders demanding greater autonomy on a variety of religious, political, and economic issues. Between 1975 and 1977, Prime Minister Indira Gandhi invoked emergency powers and imposed a dictatorial rule over the country. Sikhs were a major locus of opposition to this, and tens of thousands of Sikhs were detained, hardening opposition to the central government.

Over the next few years, Sikh opposition became partially militarized. This is a vast oversimplification, but what’s important to know is that state repression and political violence both became much more commonplace in Punjab.

This culminated in Operation Blue Star in 1984. Some alleged Sikh militants had taken refuge in the Golden Temple complex in Amritsar, the holiest place in Sikhism. The Indian military invaded without warning, and some estimates place the number of dead in the thousands, including pilgrims who happened to be in the temple at the time. The Akal Takht, the highest temporal authority in Sikhism, was also utterly destroyed.

A few months later, Prime Minister Indira Gandhi was assassinated by her own Sikh bodyguards. As a result, the ruling Indian Congress Party and the police orchestrated a pogrom that killed thousands of Sikhs in Delhi and the surrounding areas. The next year, Air India 182 was blown up by Sikh extremists from Canada.

Over the next decade, a low-level civil war raged in Punjab, during which time the Punjab Police disappeared thousands of Sikhs. Sikh refugees fled India in droves, settling in Canada, the U.K., the U.S., Australia, and elsewhere.

Since that time, violence has abated in Punjab. Support for an independent Sikh nation still exists, but is not as widespread as it once was. There are occasional terrorist attacks, but they are few and far between.

The Bharatiya Janata Party is a political party that espouses a form of hardcore Hindu nationalism. It has long been the main opposition to the Indian National Congress, which dominated the first 70 years of independent Indian history. While the Congress is socialist and secular, the BJP is capitalist and fundamentalist. The BJP believes that Islam and Christianity are foreign religions which have no place in India. And that Sikhi, Jainism, and Buddhism are not independent religions, but fall under the umbrella of Hinduism.

In 2002, Narendra Modi, who was the BJP chief minister of Gujarat, oversaw a pogrom of Muslims — the second worst pogrom in modern Indian history, after the 1984 Delhi massacres. In 2014, he was elected Prime Minister of India.

Modi’s premiership has been characterized by intense discrimination against Muslims and Christians, an erosion of the independence of democratic institutions (the media, judiciary, etc.), and arbitrary, disruptive policymaking. The government has cultivated strong ties to large business conglomerates that have benefitted from the elimination of regulations and the doling out of pork-barrel contracts.

In 2019, the Modi government eliminated Kashmir’s special constitutional status and placed the state into an unprecedented lockdown — detaining political leaders without charge, shutting down the internet, and cutting off access to outside media.

That same year, they introduced legislation that would change citizenship and refugee laws in a manner that would disenfranchise millions of Indian Muslims. This was interpreted by many to be an attack on the fundamentally secular nature of the Indian state, and led to the first major mass demonstrations during Modi’s rule. After months of highways around Delhi being occupied, the government and police colluded to attack and kill the protesters, and eventually the demonstrations were dispersed.

The ongoing Farmers’ Protests are the second major threat from the populace to emerge during the Modi era. The states in the north have historically been the breadbasket of India. It’s still largely small-plot family farms, which are inefficient but provide a livelihood for a majority of residents in those states.

In 2020, the Modi government unilaterally announced that they would be withdrawing supports for the farming sector. The thinking was that this would make the sector more attractive to investors, who would then be able to inject capital and increase yields. The farmers, especially in northern India, believe that this would destroy their livelihoods, that it was done without their input, and is essentially a payout to the big businesses that support the BJP.

Farmers began to protest, first in their home states. As the government held its line, the protests grew in number and eventually came to set up permanent encampments on the outskirts of Delhi late last year. By some estimates, this is now the largest protest in human history.

On January 26, 2021 — Republic Day, which celebrates the creation of the Indian constitution — the farmers took their protest inside of Delhi.

While the Farmers’ Movement crosses religious lines, many of the farmers are Sikh and much of the organizing has been informed by Sikhi. Time and time again, the Sikh community has formed a locus of resistance against the central government — as they did in the Mughal era and with the British Raj and Indira Gandhi’s emergency rule.

Despite the BJP’s efforts to ingratiate themselves with the Sikh community, Sikhs have remained cool towards Modi, though not openly hostile. But the Farmers’ Protests have made them a live oppositional force once again, a real threat to the increasingly autocratic central government.

This has galvanized other groups that oppose Modi and the BJP, inspiring large solidarity protests throughout India.

While the Sikh presence is an important component, the protests do cross religious lines. But it’s been in the government’s interest to portray them not only as exclusively Sikh in nature, but as Khalistani.

In the mid-1990s, Khalistani militancy came to end through a combination of state repression and the general population’s exhaustion from conflict. Over the next 20 years, the dream of an independent Khalistan faded within Punjab, though it never went away entirely. Small cells of Khalistani terrorists still operated with support from Pakistan, and marginalized political parties and religious networks still seek independence through political means. It should be noted that India also had a Sikh prime minister, Manmohan Singh, from 2004 to 2014.

But the threat of Khalistanis has continued to be invoked by politicians and the media, including by Sikh politicians, such as Punjab chief minister Amarinder Singh. The term has become synonymous with “terrorist” to a certain segment of society and is now used to delegitimize even peaceful struggles.

While the idea of an independent Khalistan has lost considerable currency amongst Sikhs in India, support has remained much stronger in the diaspora, especially amongst those who fled the violence post-1984. And that is where Canada comes in.

During the violent years in the 1970s, 80s, and 90s, Sikh sovereignty movements often found support, funding, and leadership amongst the diaspora. Both peaceful campaigns and terrorist attacks were planned from foreign soil. And because Canada has one of the largest Sikh populations in the world, British Columbia and Ontario were central locations for this movement. The most obvious example is the terrorist attack against Air India 182, but it was hardly limited to that.

Khalistani terrorist organizations were active in Canada in the 1980s and 90s. Two of them in particular actually had the capacity to carry out attacks — Babbar Khalsa and the International Sikh Youth Federation. After September 11, 2001, new laws were brought in to deprive terrorist organizations of their funding, debilitating both groups. For all intents and purposes, they do not exist anymore.

The last instance of Khalistani violence in Canada took place in 1998, when Tara Singh Hayer, a B.C. journalist who was a key witness for the Air India investigation, was assassinated.

However, the stereotype of the violent, Canadian Khalistani became a talking point in Punjabi and Indian politics. Once the militancy came to an end in Punjab, much of the blame for any ongoing violence was shifted towards Sikhs in the diaspora, and especially in Canada.

In the last 10 years, Canadian Sikhs have become a sort of bogeyman for the government-controlled media in India and for the political parties that rule Punjab. During the Stephen Harper era, the Indian government, under the Sikh prime minister Manmohan Singh, chastized Canada for allowing Khalistani organizing to take place on Canadian soil. The Harper government pushed back, affirming the rights of Canadian Sikhs to organize. (This commitment to free speech was short-lived, however; since leaving office, Harper has cozied up to the BJP and spoken out against Sikh communities in Canada.)

When there is a terrorist attack by Sikhs in India, it is often blamed on Sikhs from the diaspora.

When Justin Trudeau was elected prime minister in 2015, he appointed four Sikh MPs to cabinet. All of them came from prominent Sikh Canadian families that were viewed by India as being too sympathetic to Sikh grievances.

The press and the Punjab chief minister, Amarinder Singh, soon labelled them all as Khalistanis, and he stated that he would refuse to meet with any of them. All of this was made worse when Jagmeet Singh became leader of the federal NDP in late 2017.

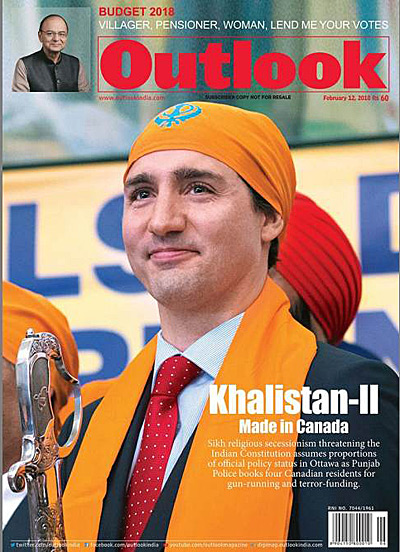

Since Trudeau’s election, the Indian media has become obsessed with the idea that a renewed, violent Khalistani movement is brewing in Canada. This is perhaps best exemplified by a February 2018 cover of India’s Outlook magazine, bearing the headline “Khalistan-II: Made in Canada” and featuring an image of Justin Trudeau wearing a Sikh head-covering.

The Indian state has had a long-term intelligence presence on Canadian soil, with a substantial impact on the Sikh community. The Research and Analysis Wing (the Indian equivalent of the CIA) has had agents operating in Sikh communities since at least the 1980s. In 1985, two RAW agents were kicked out of Canada.

Since then, it’s been an open secret that Indian intelligence continues to spy on dissident communities in the West, especially Sikhs and Kashmiris. A Scottish man named Jagtar Singh Johal has been held in India on terrorism charges for years, without any court proceedings. He says that he was tortured and forced to sign a blank confession.

A few years ago, I reported for The Globe and Mail about the Indian consulate in Toronto attempting to interfere with a Brampton cultural festival. In 2019, German courts convicted two people for spying on Sikhs and Kashmiris in that country. Last year, Global News reported that Canadian politicians had been the subjects of Indian espionage operations.

The Indian state also punishes dissidents abroad by denying them visas. Jagmeet Singh can no longer visit India because of this, and the same is true for numerous academics and journalists.

Last year, Indian authorities charged an American man who is the head of Sikhs for Justice, a diaspora group trying to organize a referendum for Sikh independence, with sedition and terrorism. There is no evidence whatsoever that he was involved in violence.

During the Farmers’ Protests, the Indian media has attempted to blame the events on Khalistanis, especially amongst the diaspora. Canadian Sikh politicians have been accused of helping orchestrate the protests in support of their alleged Khalistani agenda. Without any evidence, the head of a British charity called Khalsa Aid has been accused of the same.

A report released last week by the World Sikh Organization of Canada, titled Exposed: India’s Disinformation Campaign Against Canada’s Sikhs, identifies several recent efforts to discredit Canadian Sikhs, both individually and collectively, through stories published and amplified by a number of hyperpartisan outlets. Just last month, for example, India’s CNN-News18 misidentified a onetime Conservative candidate who attended the Farmers’ Protest as a Canadian party leader and retracted a separate report that incorrectly named a Toronto talk show host as a Khalistani-tied foreign funder of the protests.

— News18 (@CNNnews18) January 17, 2021

Arshy Mann is the host and co-producer of Canadaland’s Commons podcast.

Top screengrab from a January report broadcast on CNN-News18.