Canada’s system for recruiting and employing migrant care workers appears as though it were designed to create a permanent underclass. It shouldn’t be surprising that importing people from elsewhere and setting them to work as live-in nannies and housekeepers with precarious legal status might be conducive to fostering exploitation.

In the words of Karen Cocq of the Migrant Workers Alliance for Change, Canada’s policies set up “purposeful inequality.”

And, as with everything other than grocery barons’ net worth, COVID-19 has only made this worse.

“Care workers were among the first to be called back to work when provinces and territories reopened, and many of them never stopped working to begin with. Instead, they absorbed the incredible burden of caring for others while their own lives remained at risk,” reporter Sula Greene explains at the start of today’s episode of CANADALAND, which features her look at the system that creates such conditions and the voices of workers who’ve been directly affected by it.

One is Jhay Dulaca, originally from the Philippines, who first arrived in Toronto at 1:00 a.m. one night and found her employers unwilling to pick her up at the airport. She tells Sula:

It’s a good thing that I had asked for the address of my friend, because I didn’t expect that my employer would tell me to stay at my friend’s house. I went to my friend’s house at, you know, like 2:00, 3:00. And then it was raining. Like, I feel like, you know, like a homeless person, with my luggage, I was wet, I was waiting two hours outside.

Her new live-in situation wouldn’t be much better:

When I came to their house, the room was not even set. Like, it was like a storeroom. And when I got there, about, I think, 10:00, I had to clean up the room. And I didn’t even have a bed.

Dulaca says wasn’t allowed to eat what she cooked for the family and rarely had time to make herself separate meals:

I cooked for them, but I couldn’t cook my own food, so I had to bring cooked food that has vinegar so it will stay, even without the fridge. I was eating tuna in cans for a month.

Even when she finally had an opportunity to cook a proper meal for herself, she says she found her employers unwilling to let her store her leftovers in their fridge:

Before coming to Canada, they said that I will have a space in the fridge where I can put my food. But now it’s not allowed. So I said, “Why are you throwing away my food? I bought it, not you.”…They said that their friends are going to laugh at them if they see meat in the fridge.

For her, that was the final straw:

I felt super low, like dehumanized, you know. Like, it made me feel like “Do I really have to endure all of this?”

Harpreet Kaur, originally from India, found herself working 19-hour days in a similar situation:

They didn’t give me proper food. And they were bullying me all the time in front of people. I would say, like, “I am a human, not an animal.” They would just say, like, I’m nothing.

She says that late one night, following a dispute over money she was owed, she was thrown onto the street:

So I packed my luggage, 1 a.m. I left the house. I spent, I think, four hours in the park. There was one small park, and I was there for four hours and it was raining.

So what is it that draws workers to the program, despite such conditions being not uncommon? Human rights lawyer Fay Faraday explains to Sula:

One thing that has attracted migrant care workers to Canada is that, globally, it has the only migrant-care-worker policy that allows a possibility for applying for permanent-resident status. So for a migrant care worker who has been migrating around the globe, being able to migrate to Canada offers them a possibility of permanent status and stability, so that they can reunify with their families. When that’s the background, you can see how so many other layers of the experience that they have intensify the possibility of them being exploited.

That path to permanent residency, however, has become an increasingly uphill climb for migrant caregivers, as Canada has shifted its immigration priorities to place greater emphasis on language and education requirements. The effect, as Karen Cocq from the Migrant Workers Alliance puts it:

What these increasing requirements are doing is they are steering the immigration system away from working-class workers and towards what has come to be called “high-skilled.” But really what it is doing is prejudicing against low-wage work and forcing workers who are in low-wage work into increasingly low-waged work and into more precarious work conditions.

When the pandemic hit, one in three migrant care workers lost their job. With their tenuous immigration status and housing often tied to employment, the resulting crisis was foreseeable. Says Cocq:

We saw a sort of sudden dramatic increase in workers who lost work, had no income, could not find a new employer, and had nowhere to live. And so we had workers who were couch-surfing with acquaintances or friends, a lot of workers who ended up in the shelter system, and who did not qualify for many of the services and supports that a lot of other workers can rely on.

But the solution, she says, is not necessarily that complicated:

First and foremost, the demand from workers — and not just care workers, but from all migrant and undocumented workers — is to have full immigration status now. Workers’ status is the category that dictates working conditions and living conditions, access to services, access to basic rights. And the fact of not having full immigration status is what creates different classes of workers. So it produces purposeful inequality in society and in the economy that puts workers at a disadvantage, that puts migrant and undocumented people at a disadvantage, and prevents them from being able to access the things that they deserve and the rights that they do have.

Interviews have been slightly edited and condensed.

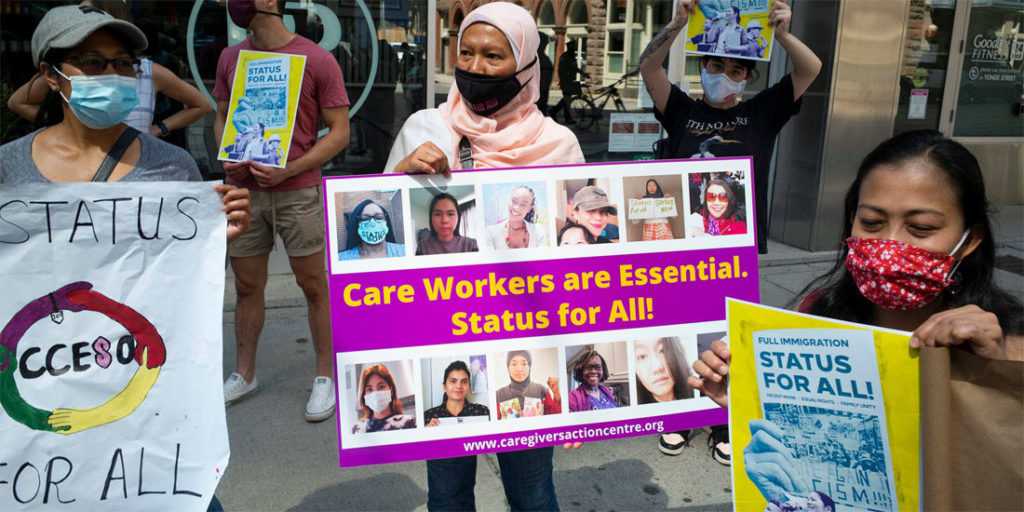

Top photo from a Status For All rally outside the Immigration and Refugee Board in Toronto last August, via the Caregivers Action Centre and Migrant Workers Alliance for Change. Dulaca is at right, holding the yellow “STATUS FOR ALL!” sign.