Private broadcasting is supposed to be diverse under Canadian law, but the government doesn’t require that companies publish their employment equity numbers.

Because of weak and inconsistent reporting guidelines, it is impossible to know the racial makeup of of private Canadian broadcasting—or whether their diversity expectations are being met.

Under the the Broadcasting Act, the bible of Canadian media regulations, private broadcasters are expected to serve and reflect the multicultural and multiracial realities of Canadians through “programming and employment opportunities.” About one in five Canadians identifies as a visible minority and more than four per cent identify as Aboriginal, according to Statistics Canada.

Private broadcasters share a few numbers in their diversity reports to highlight the success of their initiatives, and some volunteer corporation-wide numbers, but they don’t need to track their newsroom’s annual equity statistics. The public broadcaster keeps its own internal statistics, which show that the CBC is about 90 per cent white.

It’s impossible to compare statistics between different companies, according to Ryerson University researcher and professor Charles Davis.

“We’ve been through a hundred or so of those [cultural] reports,” Davis said, adding that while some broadcasters only file their initiatives, others report on-screen diversity, and still others behind-the-scenes numbers. “So you can’t really track it from year-to-year.

“The problem is inconsistency in the [CRTC’s] reporting requirements.”

Davis is the E.S. Rogers Sr. Research Chair in Media Management — in 2011 and 2012, he was part of a research project and follow-up roundtable that addressed the participation of visible minorities in screen-based media. He said the CRTC should eventually require companies to provide separate numbers for their media counterparts so they can track the shift, or lack thereof, in newsroom diversity. “CRTC doesn’t really have jurisdiction over employment equity, so I think that’s a problem.”

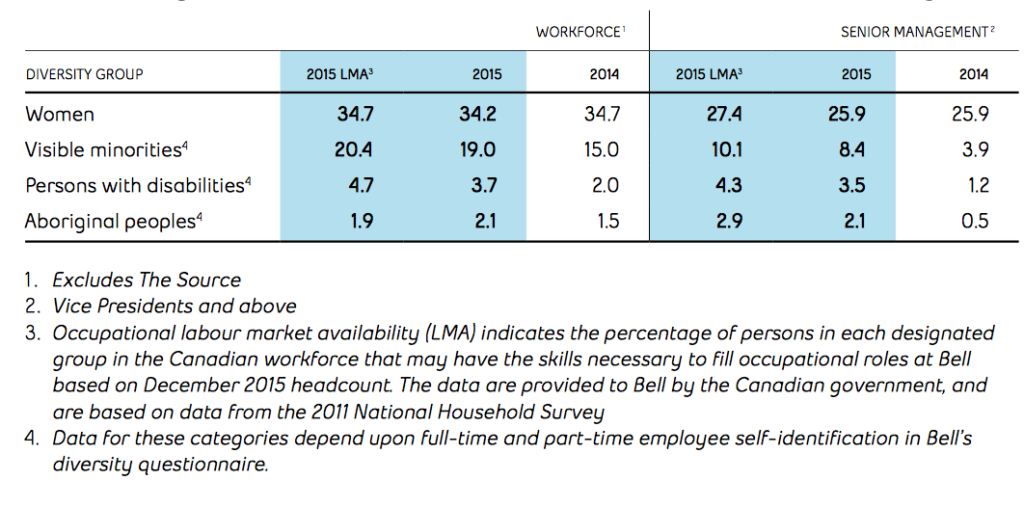

Broadcasters that have more than 100 workers file their employment numbers under the Employment Equity Act to the Human Rights Commission, and not to the CRTC. The racial makeup of Canada’s broadcasters is largely buried in the company-wide statistics of Bell, Rogers, and Corus. The diversity statistics for their media divisions aren’t broken out, so there’s no way to tell how diverse the on-air product is.

“We were interested in diversity in a creative occupation, whereas you find probably more diversity in a technical occupation,” Davis said. “So when they provide aggregate numbers, it doesn’t really show where the diversity is and where it isn’t.”

For example, BCE publishes its company-wide equity numbers every year. But it doesn’t publish separate numbers for its Bell Media subsidiary, which produces MUCH, CTV, and numerous other channels. Bell Media employees make up about 13 per cent of the BCE’s 50,000-person workforce.

“We publicly report numbers for Bell overall but not for specific business units,” said Scott Henderson, Bell Media’s vice-president of communications. “Reporting an overall number for Bell gives a far better reflection of our progress as a company.”

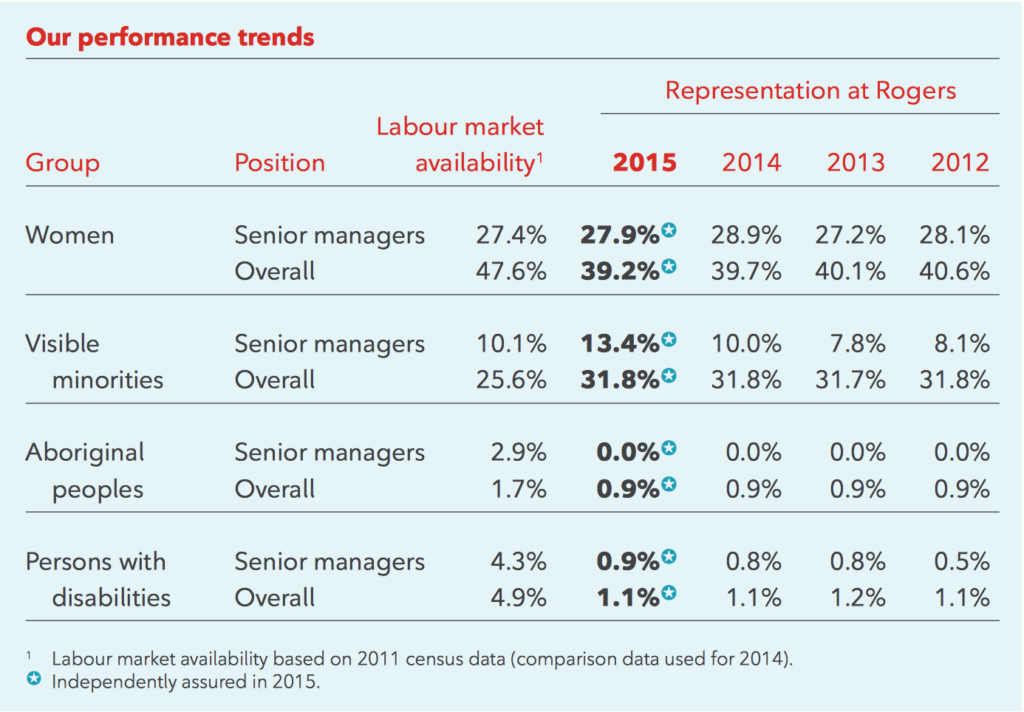

Bell’s chief competitor, Rogers — whose media holdings include City, OMNI and Sportsnet — also leaves out employment equity numbers for its media subsidiary in its report.

According to Rogers spokesperson Andrew Garas, Rogers Media employees make up about 20 per cent of the total Rogers workforce, but the Broadcasting Act doesn’t force them to publish media-specific numbers.

“The Broadcasting Act itself does not set out the reporting requirements, just merely indicates that the broadcasting system should reflect cultural diversity in employment opportunities,” Garas said in an email.

Nanao Kachi, the director of CRTC’s Social and Consumer Policy, said in an email that private broadcasters must file Corporate Cultural Diversity Reports in order to “report annually on [the broadcaster’s] progress on these diversity issues.” These documents set best practices and equity goals.

In 1992, the CRTC made diversity an element of licensing, saying the designated groups — women, Aboriginal persons, disabled people and members of a visible minority — continued to face “underrepresentation, high occupational concentration in clerical jobs and wage disparity” in the communications sector. It later clarified companies already covered by the Employment Equity Act wouldn’t need to answer for their employment equity practices at licensing.

The most comprehensive study of diversity in the broadcasting industry was commissioned in 2001, when the CRTC called upon the Canadian Association of Broadcasters (CAB) to form a task force to report on the cultural diversity of Canadian television, partly to set a baseline to improve upon in the following years. Four years later, the CRTC responded to the task force’s findings and said mainstream media lacked fair representation.

“Most participants perceived Asians, the largest visible minority population in Canada, as being severely underrepresented,” the CRTC said in the notice, adding that the appearance of Hispanic and Middle Eastern people was “sporadic” while Black people were better represented thanks to U.S. programming. The most pressing issue, as noted by the task force and the CRTC, was “the virtual absence of Aboriginal peoples in all genres of programming” outside of APTN. “In 10 of 11 genres studied across two languages, the presence of Aboriginal Peoples is less than one per cent of the total,” the notice said.

More than a decade since the study, no follow-up or similar report has been commissioned by the government — according to Davis, the lack of “systematic study of on-screen diversity” since 2004 has added to the problem of inconsistent reporting guidelines. However, he said that from what he understood, the CRTC is in the process of hiring a company “to sample on-screen programs and then to figure out how to measure diversity.”