The idea that WE Charity was uniquely capable of executing the government’s $912m student volunteer program is challenged by an analysis of their audited financial statements by Charity Intelligence (CI), an independent charity watchdog group that helps donors “give intelligently and have impact with their generosity.”

CI’s legitimacy as a neutral authority on the charitable sector was recognized by none other than WE Charity itself, who previously used its CI rating to challenge Canadaland’s investigation.

“The information shared by Canadaland in its questioning about budgeting, data and numbers is incorrect….Charity Intelligence Canada awarded WE Charity a perfect four-star rating.”

-Victor Li, CPA, CGA, CFO, WE (May 17,2019)

When the pandemic began, WE Charity promptly laid off the majority of its workforce. Media reports assumed that this was a direct result of COVID-19, with its obvious impacts on donations and live events.

But in an interview with Canadaland, CI’s Managing Director Kate Bahen shares information from WE’s own audited financial statements that tells a different story – one of an organization that appeared to already be in crisis and making strange financial transactions when COVID hit, to anyone who bothered to look.

***

Jesse Brown: Kate, what was the first inkling you had that all was not perfect with WE Charity?

Kate Bahen: I’m glad that people wave those star ratings around. But when you scratch beneath the veneer, there were lots of red flags. I hope that donors would read what was actually written in the text.

J: Your practice is based on numbers. It’s based on going through their audited financials line by line. What is it in their audited financial statements that raised concerns for you?

K: You could see the real estate holdings right there on the balance sheet. You could see the properties. This wasn’t a charity that had a lot of cash…It was investing heavily in real estate. The concern was also the leverage.

When you build a hospice, when you build a homeless shelter, you will go into debt very often and you will have a long term mortgage with regularly scheduled payments. But all of WE Charity’s debt was short-term, non-revolving, demand loans, at the beck and call of the banks. But it was the amount of debt on these properties. And it was always changing. So we always looked at the debt levels.

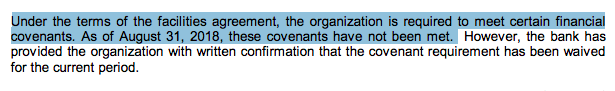

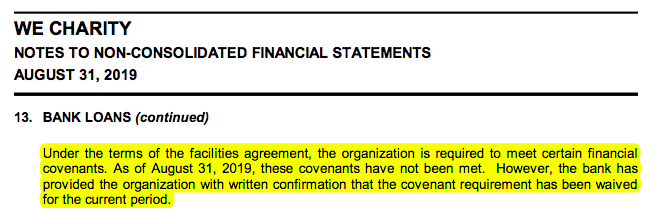

And then in 2018, the auditor flagged for the first time that WE Charity was in breach of its bank covenants. That is a massive, massive red flag. I have never seen that on any other charity in its audited financial statements.

J: For those of us who are less financially literate, when you say they’re in breach of their bank covenants — they’re racking up big debt to the bank while they’re buying major pieces of property. Am I getting that right?

K: It’s leveraged, they’re not using cash.

Some people live a certain lifestyle and you only ever see one side of the balance sheet. You don’t see how much debt that person has. WE Charity had the big offices, had the Global Learning Center, had all the assets, properties on Queen Street, but these were all backed — its lending practices were getting close to the max. Kind of like your credit card. You know, if you’ve got a credit card limit of ten thousand dollars, these guys were always at nine thousand five hundred. It was always pushing, pushing the limits.

So it was you know, [they] have to go to the bank every year and renegotiate this loan. God forbid the bank says ‘no’ this year. It’s kind of like a high wire act. It just isn’t seen in charities. So WE is different on so many fronts.

J: Your analogy to a soup kitchen or a hospice — those are facilities that directly do charitable work. The Toronto SUN’s Brian Lilley reported that WE quickly acquired $38.7m in Toronto real estate. How much money were they spending each year on their actual charitable works instead of on their headquarters and things like that?

K: That’s not disclosed. So I don’t see that. Let’s say that they bought a building on Queen Street for three million dollars to help children in Ethiopia, and they declare that the property is for that overseas work. Well, we are analysts, not auditors.

J: Any other [concerns]?

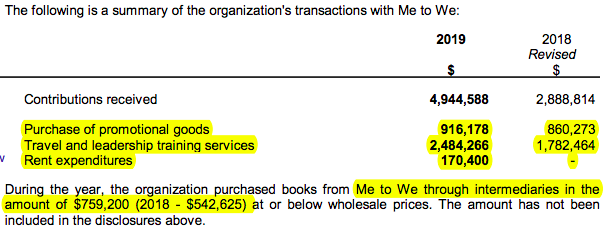

K: Related party transactions. So (the for-profit company) ME to WE is related to WE Charity by the two founders, Craig and Marc Kielburger. What ME to WE was giving to WE Charity and what WE Charity was paying ME to WE is a related [party] transaction and it needs to be reported. There’s a professional obligation by the auditors to report those.

It wasn’t just ME to WE, it’s very convoluted between holding companies and subsidiaries. It just didn’t make any sense.

In 2016, there was the WE 365 app and teachers were told that if you get kids to download this app, for every download a child will get vaccinations.

But the app didn’t work and it was glitchy. And, now if you go to the App Store and try and download it, there is no such thing as WE 365 to download.

But, you know, it was sold to WE Charity [by WE 365] for one dollar and all the debts incurred in creating this app that doesn’t exist anymore [now belonged to WE Charity], which is just bizarre.

J: That’s significant.

K: No, it’s not! We’re just talking about a $265,000 transaction at a $60m charity. Let’s focus on the $4.9m of debt that WE Charity had to pay the banks in May 2020. And it’s got another $4.3m due at the end of October. So let’s focus on the big numbers.

J: Ok, let’s focus on them. Were those dates determined before the pandemic? Were they in that kind of financial trouble before COVID?

K: Yes! And that’s what I’ve been sort of jumping up and down on the government’s due diligence. Before you give them an agreement to distribute $912m dollars, look at the board of directors.

Did WE Charity inform the government that its board had resigned or was replaced just weeks before, and that there was a gap in governance and oversight at the charity?

And if you read the audited financial statements, there it is in black and white, WE Charity is in breach of its bank covenants. Oh and by the way — it has no board.

J: Everything you’ve said so far might describe an organization that had a folly with an app that didn’t work out, that maybe got overambitious with its spending on properties. But that doesn’t really explain the other side of this, which is that money was flowing from charity to private company, in the opposite direction that it was supposed to.

K: The backwash. ME to WE backwash.

J: You have been public that in 2019, the same year that found them in breach [with the bank], that same year when they needed money, seven percent of all WE Charity’s revenue flowed to their privately held company.

K: That had grown. Before, it was one percent, two percent. What you see is them ramp up in fiscal 2018 when eight percent of WE Charity’s total revenues are going into the private business and in 2019, seven percent. And you’re dealing with a 60 million dollar charity here, so we’re not talking chump change.

J: Kate, people have said to me there’s nothing to see here. Sometimes a charity has to buy a few things from its related business. That’s true, isn’t it?

K: Yes.

J: So what’s wrong with this?

K: It’s the magnitude. Some private corporations play a little hard with their charities and say, you know, ‘we want you to pay the going rate’ and all the rest of it. But it’s [typically] a few hundred thousand dollars on a six million dollar charity. It’s not like this.

J: Have you ever seen this level of backwash?

K: No.

J: You would think that in the year when all their debts are due, that would be the year when they need to keep that money in the charity. But instead, they’re flowing it into their private company.

K: Yes

WE Charity’s response:

In the most extreme and, frankly, inaccurate, calculations, if someone dismisses (i) removed all value from the purchase of ME to WE services; (ii) removes all in-kind contributions from ME to WE, then WE Charity has still received $1.3-million more from ME to WE over the last five years.

J: Their argument has been: If you look at this the right way, overall, the charity comes out on top. Overall, the charity is benefiting from this relationship. Is that true?

K: The level of disclosure in their audited financial statements does not allow me to verify that claim.

J: You don’t have the information you would need to say, ‘yeah, that looks right.’

K: What it does say in the audited financial statement is not that ME to WE “donates” to WE Charity but that ME to WE “contributes” to WE Charity.

J: What’s the difference?

K: A donation is money. A contribution can be time, money or goods.

J: So when the WE Charity pays the Kielburgers’ private company, they pay in cash. But when their private company pays the charity, it’s a mixture of money, time and other benefits — and we don’t know the mix. Is that correct?

K: That’s correct.

J: If WE’s auditor were to dig down on that, you might find that everything’s fine. That in fact, it is cash going back to the charity. Or you might find that there’s no money or very little.

K: KRP have audited the books of WE Charity since these teenagers from Thornhill began over 25 years ago. It specializes in tax and small businesses. I believe WE Charity is the only charity it audits.

J: Well, that is weird.

K: It’s unsettling.

J: Back to the board of directors. WE has said the former board members were almost done their 5-year terms, and WE wanted a refresh. Is that not a credible explanation?

K: If a charity was to take the strategic decision to radically replace its entire governance structure, that needs to be signaled to donors and corporate sponsors well ahead. That needs to be posted on a web site. Everybody needs to know what’s going on, so that it isn’t a surprise that you find out on Twitter that the chairman of the board resigned in March…and since the chair of their board resigned, that doesn’t jibe with their story.

So you have an unprecedented turnover in governance that was not signalled.

When you have a scandal or a crisis at an organization, it’s the chairman that steps up and testifies in front of Congress. It’s the board chair who steps up and takes the mike.

And now we go into a crisis with a rookie slate of directors.

Almost all of the board of directors of WE Charity in Canada and the US) resigned or was replaced in March 2020. https://t.co/jtKInVhNa0

— Michelle Douglas (@MDouglas_YOW) June 29, 2020

J: The new board of directors, as I understand them, have long relationships with the Kielburgers. The new chair of the board, Greg Rogers, was Marc Kielburger’s high school teacher.

K: It’s a mismatch.

J: Did something happen for this sudden turnover in the board? When I look at all of these things together — not only do they have all this debt that’s coming due. At the same time, they’re flowing money out of the charity, into their private company. And then the board leaves. Do those all seem to you like discrete and unrelated events?

K: I guess it’s a compilation. Jesse, it’s just too many things.

***

With research assistance from Tiffany Lam

UPDATED (07/27/2020) to clarify that the kind of debt Bahen describes as non-revolving, not revolving.