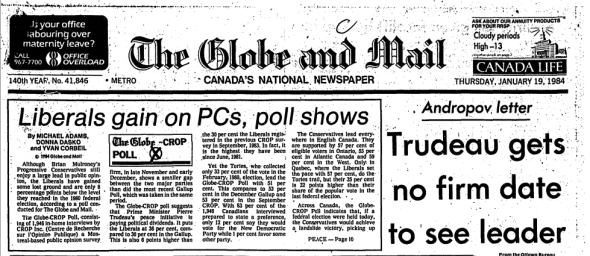

On January 19, 1984 the Globe and Mail published the results of an opinion poll above the fold on its front page. Nothing about the results of the poll, conducted on behalf of the Globe by the Montreal-based firm CROP in collaboration with Environics, was particularly striking: the Liberals, then led by Pierre Elliott Trudeau, appeared to be gaining on Brian Mulroney’s Conservatives and the NDP was faring poorly.

What was striking was its presentation. Running alongside a more than 1,000 word article breaking the results down in detail, the poll was also accompanied by an analysis from its authors explaining their methodology and putting its conclusions into context.

Opinion polling has enjoyed a slow but steady ascendency in Canadian political journalism. During this close federal election, polls have dominated coverage as the country watches for predictions of outcomes. In the 1980s, pollsters like Martin Goldfarb and Allan Gregg, who had both begun their careers as partisan political operatives – Goldfarb for the Liberals, Gregg for the Progressive Conservatives – became pundits in their own right.

In the age of social media and 24-hour news, polls have come to dominate political reporting not only during elections, but between them as well. Naturally, this has created problems.

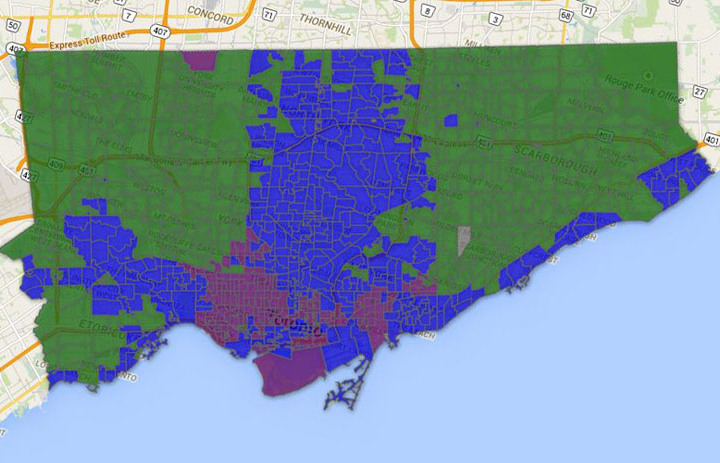

I recently decided to investigate the use of polls in Toronto’s 2014 mayoral election, and especially how newspapers reported on them. The results weren’t particularly inspiring and reveal a lot about the ways in which polling now exercises a disproportionate influence, both over political journalism and electoral politics.

While I looked at the use of polls over the campaign as a whole, my investigation focused most on the reporting done by the Toronto Star, the Globe and Mail, and the Toronto Sun in the final month of the campaign (September 27-October 27, excluding election day). Between these dates by my count, ten mayoral polls were reported on in the media out of a campaign total of thirty-three, making it an especially clustered period.

On the face of it, ten polls might not sound like a lot for a twenty-nine day period.

Each poll was generally published as a distinct story with some accompanying information about its sample size and margin of error, and some limited analysis from an individual pollster (generally running about 500 words). In the Toronto Star, which did by far the most reporting on the campaign, I counted twelve stories of this kind: that is, specifically about a poll or comparing the results of different polls. In the Globe and Mail I found six, and in the Toronto Sun five. So far so good, or mostly.

But these ten little polls managed to reach far beyond this relatively small cluster of stories. In the Star alone, for example, I found a total of seventy-three distinct articles making reference to polls in just this twenty-nine day period (nineteen of these in op-eds and editorials, the rest in general reporting) meaning they had a presence in the paper every day, and then some.

What’s more, they seemed to make their way into stories about particular campaign issues with little to no need for a horserace backdrop. An October 2nd article in the Star about racist and sexist comments on Olivia Chow’s Facebook page, to take one example of many, actually led with a reference to the polls. Or, to take another, an October 14th report in the Globe focused on the campaign debate over transit funding partly framed its subject matter around recent polls.

If it sounds like I’m nitpicking, consider this: In the vast majority of their appearances in all three newspapers, “polls” were referred to without any specific reference or link to actual polling data. In this way, the reader is increasingly encouraged to think about them as objective facts rather than one part of the wider ecosystem of electoral reporting with potential problems and grey areas like any other. It would not be an exaggeration to say that in the final month of the Toronto mayoral election, ten opinion polls took on a life of their own and bent much of the reporting on other events and issues around them. We have little reason to believe this pattern will shift before the upcoming federal election and the maelstrom of polling that will be reported alongside it.

Thanks to technology, polls are now substantially cheaper and easier to conduct, meaning journalists hungry for copy have a ready-made source, almost whatever the occasion. Whereas the Globe’s January, 1984 poll asked people a series of questions in person, today’s polling companies rely heavily on Interactive Voice Response (IVR), better known as “robocalling”, to reduce their costs. IVR polls, often built around the assumption of low response rates and even shorter attention spans, generally ask fewer questions and harvest less qualitatively detailed information. They also accounted for the vast majority of the polls in the 2014 mayoral election.

Polls can now be conducted and published with such frequency that the process of either reporting on a campaign or forming an opinion often has more to do with what the polls may be telling us than anything else. Before most of us have time to formulate an opinion, we’re already having one served back ready-made in the form of an opinion poll or an article framed around one.

Many polls ask a [relatively small] sample of us how we’re planning to vote, without asking why. As the Star’s Catherine Porter pointed out in an October 20th column, only one conducted in the final month of the campaign actually asked respondents for qualitative answers beyond their voting preferences. Not only does this produce narrower and less interesting data, but it discourages us as voters from thinking about the actual reasoning behind these preferences. Put another way, the “what?” is obstructing the “why?”.

And, in any election, the “why?” question is surely the most important one that journalists and voters should be asking.

CORRECTION: An earlier version of this article erroneously said the Liberals were led by John Turner at the time. In fact, Pierre Elliott Trudeau was the Liberal leader. John Turner was elected to head the party in June 16 of that year.