Emails obtained by CANADALAND reveal a week of confusion and anger inside McGill University, following the publication of Andrew Potter’s controversial Maclean’s article that referred to Quebec as “an almost pathologically alienated and low-trust society.”

Within two days, Potter resigned from his post as head of the McGill Institute for the Study of Canada (MISC), but kept his temporary contract as a professor.

The 688 pages of email exchanges, released under access-to-information laws, give new insight into how the school’s crisis spiralled out of control, as donors pulled funding, administrators fended off reporters, and the Prime Minister’s Office bristled at having been dragged into it all.

The documents show various actors putting pressure on each other — rather than issuing outright instructions — but appear to corroborate the university’s previous statements that administrators were not directly strong-armed by politicians. They also provide no proof that Potter’s superiors pushed him to resign — yet simultaneously suggest that he hadn’t planned on doing so.

Here’s what happened behind the scenes at McGill after Potter’s article was posted on the evening of March 20:

Senior administrators awoke to a handful of angry emails in both official languages, which cascaded into dozens of messages by the afternoon; the vast majority decried Potter’s piece.

“It is violent, exaggerated, the article contains a panoply of falsehoods; in short, a typical example of ‘Quebec bashing,’” a former McGill employee wrote in French, hoping that Potter would “be held accountable to his peers.”

By midday, Premier Philippe Couillard told reporters it was an article “of very poor quality,” prompting McGill’s communications head Louis Arseneault to notify his colleagues.

“Potter should not have associated himself with MISC on the article,” replied Susan Aberman, the principal’s chief of staff, who appended to her email McGill’s Statement of Academic Freedom, which advises scholars to “represent their views as their own” in non-academic debates.

At 12:42 p.m., Arseneault sent an email noting that arts dean and former MISC director Antonia Maioni “spoke with Andrew Potter. He said he is sorry about the impact of his text and will apologize, on social media notably. He will send his message to Antonia and she will share it with us. I will forward it to you along with our proposed Twitter message for approval.”

It’s not clear from the documents whether administrators started crafting a message for McGill’s Twitter account before or after they knew Potter was going to apologize.

The complaints persisted, with an “appalled” alumnus suggesting that McGill “distance itself” from Potter for writing “insulting and baseless opinions” while head of the institute. “How McGill University let that one slip is quite frankly hard to believe.”

A McGill professor, whose name is redacted in the documents, said it was “unacceptable” that a MISC director “should be so ignorant and irresponsible … I hope that the University will do what is needed to restore the respect” for the MISC.

A member of the public asked McGill if the university hated Quebec: “If this text was about a Black or Jewish people rather than Francophones, it would be considered racist.”

But the response wasn’t all negative. An ambitious stranger with a bachelor’s degree asked Potter about completing a research paper on failures in governance, tying together police spying on Montreal journalists, the “botched” amalgamation of Quebec cities, and the province’s 2012 student protests.

Potter posted his public apology to Facebook at 1:28 p.m.

At 1:54 p.m., McGill’s Twitter account shared a message in both official languages: “The views expressed by @JAndrewPotter in the @MacleansMag article do not represent those of #McGill.”

This was quickly followed by online mockery and an outcry concerning a chill on free speech.

Senior administrators seemed baffled by the response: “The Twitterverse has lit up like a Christmas tree,” lamented Doug Sweet, head of internal communications.

At the same time, Potter informed his colleagues that he was set to host an event that evening, the Eakin Lecture on Free Speech in a Multicultural Democracy. “I’m getting a LOT of reporters calling for interviews, and I’m fairly certain someone will show up,” he wrote. “I think it would be bad if I got buttonholed [cornered] by a reporter or a photographer; it could undermine the event and hurt the school.”

Potter suggested administrators either cancel the event or find another host. They ultimately chose his recommended substitute, history professor Elsbeth Heaman.

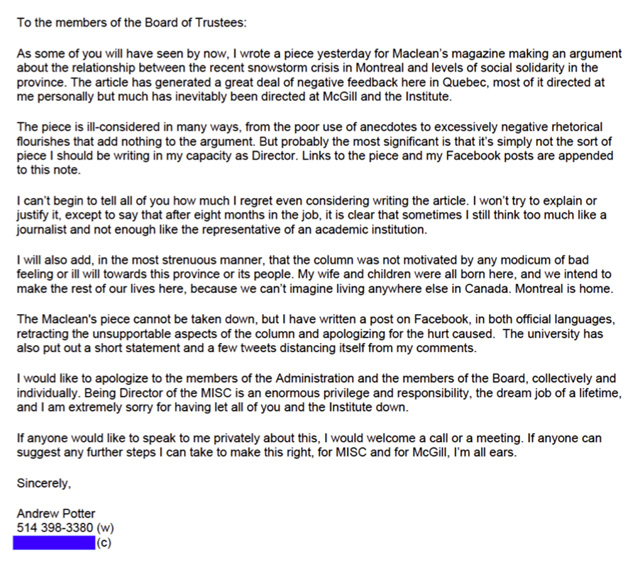

At 5:45 p.m., Potter sent an apology to the MISC board of trustees for his “ill-considered” piece. “It is clear that sometimes I still think too much like a journalist and not enough like the representative of an academic institution,” he wrote.

“The Maclean’s piece cannot be taken down,” Potter noted, but he gave no indication he’d considered resigning. “If anyone can suggest any further steps I can take to make this right, for MISC and for McGill, I’m all ears.”

That evening, Alain Dubuc, a business columnist for La Presse who sits on the MISC board, told Potter that “this incident will not help the MISC, and it will not help McGill University in its efforts to strengthen its links with Quebec.” Roughly 10 lines of the email were redacted, under access-to-information exemptions for personal information.

At 7:04 a.m., McGill’s social media head noted that “our tweet got a lot of harsh criticism on social media last night.”

But Aberman, the principal’s chief of staff, dismissed the feedback. “He was speaking as a McGill administrator and not as a professor,” she told colleagues.

As the onslaught of emails continued, Derek Cassoff, the head of alumni communications, asked for guidance in responding. “We are now starting to receive emails from alumni, mainly Francophone, who are upset over Andrew Potter’s op-ed in Maclean’s. In most cases, they are asking that McGill no longer contact them and purge them from our mailing lists.”

Among them was a Quebecois lawyer who expected “more rigorous intellectual positions from people who should be part of McGill’s elite.” Another member of the public said he felt “ashamed that a Quebec university could employ someone who has no respect for Quebec society.”

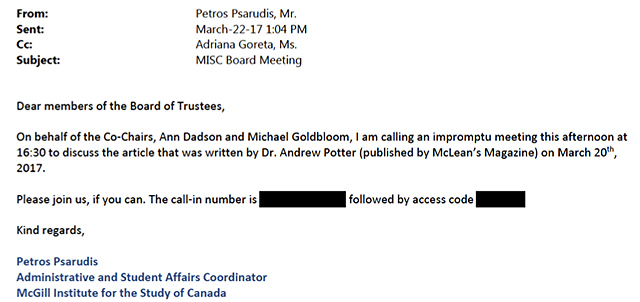

At 1:04 p.m., the MISC board called an emergency meeting for 4:30. The documents include no emails between Potter and McGill principal Suzanne Fortier.

But in a statement sent last week to media, including CANADALAND, communications chief Arseneault wrote that Potter had asked to meet with Fortier on March 22 and submitted his resignation to her that day.

“Professor Potter was assured that his appointment as Professor was not under question. The discussion was about his ability to continue in his role as Director of MISC. He himself acknowledged that the creditability [sic] of the Institute would be best served by his resignation. The Board of Trustees of MISC accepted his resignation later that day,” Arseneault wrote.

This week, he stressed in an email to CANADALAND that neither Fortier “nor anyone else asked Prof. Andrew Potter to resign from his position of Director of the McGill Institute for the Study of Canada.”

Hours after both the MISC board meeting and the private meeting between Potter and Fortier, rumours of Potter’s resignation pervaded the university. Maioni, an ex-officio member of board, told senior administrators at 6:57 p.m. that a Globe and Mail reporter claimed to have “a few sources” saying that Potter had resigned and was seeking confirmation.

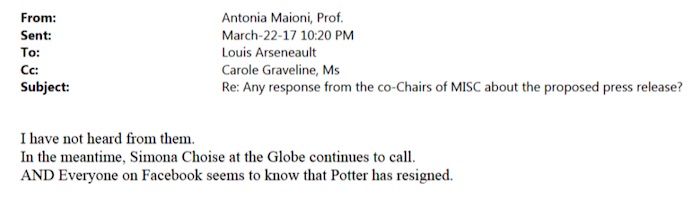

At 10:15 p.m., Maioni wrote to a colleague about a Facebook post by law professor Daniel Weinstock, quoting it as saying that “Potter was asked to resign a few hours ago.” She asked: “Has Andrew already told everyone?”

Five minutes later — in an email thread concerning whether the board chairs had yet signed off on a news release announcing the departure — Maioni wrote that “everyone on Facebook seems to know that Potter has resigned.”

At 11:08 p.m., Aberman and Fortier submitted their own edits to the release.

Thursday morning, Maioni told Potter the release would soon be published, and advised him to only say goodbye to his MISC colleagues “with the caveat that this be kept confidential until the press release hits the wires.” She also started planning a possible new job for him.

“I am already thinking about next steps, including the possibility of reviving a Media Observatory in the School of Public Policy, which would of course greatly benefit from your experience and expertise,” she wrote.

Meanwhile, rumours on Twitter suggested that the Prime Minister’s Office, the Quebec premier and/or Montreal’s mayor had asked for Potter to resign, prompting more than a dozen media inquiries from outlets including CANADALAND.

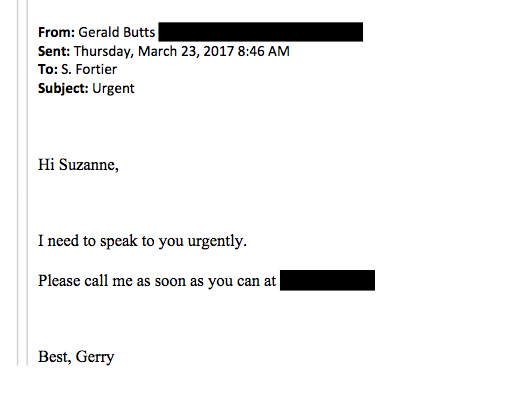

That morning, Gerald Butts, senior advisor to Prime Minister Justin Trudeau, wrote to Fortier: “I need to speak to you urgently. Please call me as soon as you can.”

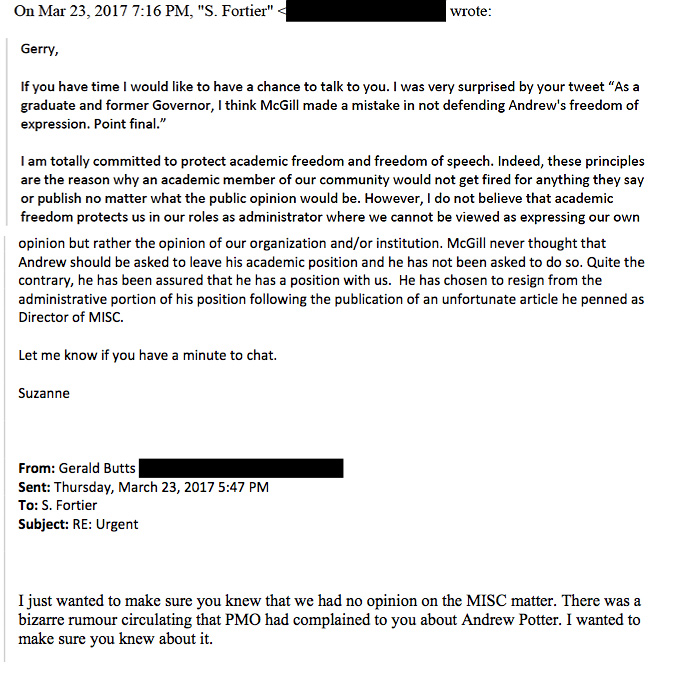

After failing to connect with Butts on the phone, Fortier messaged to ask if he still wanted to talk.

Butts got back: “I just wanted to make sure you knew that we had no opinion on the MISC matter. There was a bizarre rumour circulating that PMO has complained to you about Andrew Potter. I wanted to make sure you knew about it.”

In response, Fortier chided Butts for a critical tweet he’d sent.

In a public message announcing Potter’s resignation to “members of the McGill community,” Fortier stressed that the university upholds academic freedom.

But that failed to convince the McGill Association of University Teachers, whose head Terry Hébert wrote: “I keep hearing he was fired. I have been saying he resigned but that we at MAUT are concerned about the academic freedom angle of things. I was hoping you could provide some insights.”

That afternoon, a MISC administrator informed the institute’s board of trustees about Potter’s resignation, and added that “any media inquiries you receive in your capacity as a MISC Trustee may be redirected to” Arseneault. At least two board members, Franca Gucciardi and Daniel Holland, then started forwarding interview requests to senior administrators.

Potter’s resignation did placate some donors. “I have new reasons to appreciate McGill,” wrote one, who reversed their decision to stop contributing.

But Cassoff, head of alumni communications, warned that the resignation was also having the opposite effect: “We are now beginning to receive emails from alumni upset about McGill’s treatment of Andrew Potter and the violation of academic freedom.”

And despite working inside the university, even Cassoff wasn’t clear whether Potter chose to step down. “I will confer with central. Not clear if he came to this decision on his own or was urged to step aside,” he wrote.

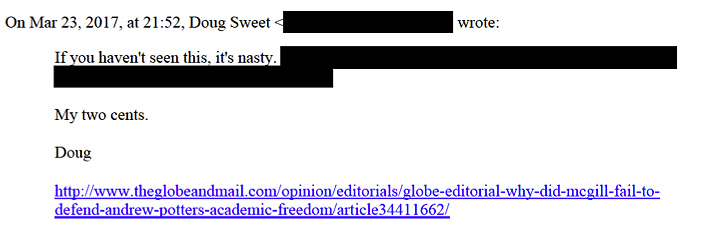

That evening, McGill’s top brass took note of a Globe editorial slamming McGill for its stance on academic freedom. Internal communications head Sweet emailed his colleagues: “If you haven’t seen this, it’s nasty.”

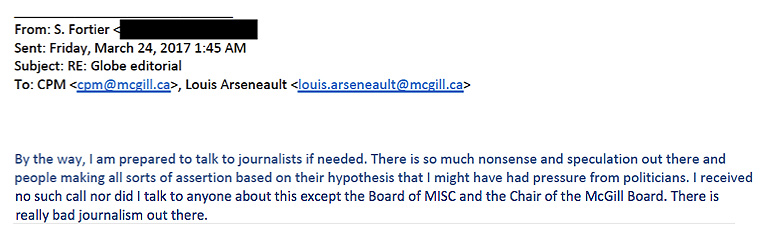

The editorial prompted Fortier to finally cave to interview requests, according to a 10:45 p.m. email. “I am prepared to talk to journalists if needed. There is so much nonsense and speculation out there and people making all sorts of assertion based on their hypothesis that I might have had pressure from politicians,” she bemoaned.

“There is really bad journalism out there.”

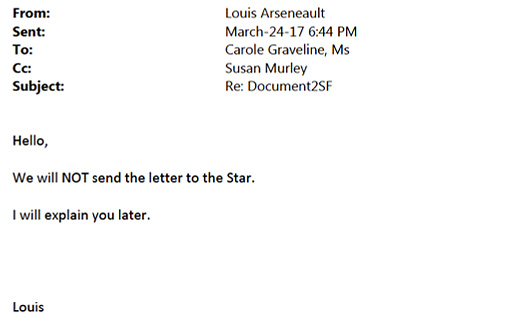

The next morning, Aberman suggested Fortier break her silence and give the Globe’s postsecondary education reporter, Simona Chiose, an interview.

Emails from angry alumni and donors continued. One cancelled a scheduled meeting because of the “unfair and unprincipled treatment” of Potter. An official responded with the previous day’s statement on academic freedom, which the donor found insufficiently persuasive: “Sorry but I’m not satisfied. Please remove me from your list forever.”

At 2:56 p.m, an unnamed faculty member wrote to senior administrators, “We have gone from a situation where the credibility of one academic was at stake, to one where the credibility of our entire institution is at stake.”

That afternoon, Maioni asked Arsenault if she should agree to an off-record interview with the Globe’s Les Perreaux, who “wants to reconstruct what happened.” Arsenault replied to Maioni: “What would be your narrative if you spoke to Les?” There is no subsequent response in the documents, and Perreaux has not since written about the incident.

Media requests persisted, with CBC’s The Current asking Maioni to join an upcoming panel about the incident. At 3:16 p.m., she declined, taking issue with its premise: a debate about who is allowed to criticize Quebec.

“Everyone is allowed to criticize anything, but there are degrees of freedom that matter. Evidence matters. And so do job descriptions,” she wrote to the producer, suggesting Potter had “distinct administrative responsibilities.

“Pinning your show on ‘who is allowed to criticize Quebec’ is, frankly, absurd.”

As the week came to a close, Hébert, from the faculty association, asked Potter and McGill management to explain “the role of the administration in the chain of events preceding his resignation.”

Hébert noted his group planned to discuss at an April 20 meeting “whether the McGill administration should comment on any opinion expressed by academics, however controversial.” Now the group is still seeking answers, recently telling the Globe the incident put a tangible chill on academics studying controversial topics.

Potter did not respond to CANADALAND’s request for comment. But four days after the controversy erupted, Potter told a colleague he hoped things would one day return to normal.

“I’d like, more than anything, to be able to erase all of this,” Potter wrote, in French. “Things got out of control in a manner I couldn’t have imagined.”

Dylan C. Robertson worked at the Ottawa Citizen during Potter’s time as the paper’s editor-in-chief, and occasionally completed assignments under Potter’s direction.