On Saturday, photojournalists Ryan Taplin and Tim Krochak walked away from the Atlantic Journalism Awards as winners. They were two of the six nominees from Local Xpress, an online protest outlet created by striking employees of the Halifax Chronicle Herald.

The Herald, normally an AJA favourite, entered the weekend with only three nominations and left with just a single trophy.

This wasn’t completely a surprise for the Xpress, given that their photojournalists received every nomination in the feature photography category, and so had that one locked up. But the wins at the ceremony in St. John’s were vindication for unionized newsroom employees who’ve been on strike for the last 16 months.

At the same time, it’s safe to assume that Krochak, Taplin, and everyone else involved with the Xpress would prefer if it ceased to exist.

“Local Xpress was never supposed to last,” says Krochak in an interview after his win. “I’ve had really fucking low points over this strike. And my fellow strikers are the ones picking me up.”

In a letter to readers posted on LinkedIn last summer, Herald CEO Mark Lever called the union’s offer at the time “a contract rooted in the past with no vision for the future” and touted his anti-labour position as a matter of keeping pace with the demands of the modern age, moving from “a print past to a digital future.”

Recently, Lever has doubled down on his plot to innovate, ideate, and buzzwordify Atlantic journalism into a more profitable venture. His company just renamed itself “SaltWire” and bought every Transcontinental Media newspaper in Atlantic Canada — promising to “challenge and reshape the media model.”

And while many have criticized the Herald’s scab skeleton crew for a slew of errors while the newsroom continues its strike, Lever has called the replacement workers “talented journalists” who “continue to meld as a team and to break the news that’s important to Nova Scotians.”

Claire McIlveen, an editorial writer on the bargaining committee for the Halifax Typographical Union (HTU), which represents Herald employees, says that’s “a load of bullshit … I think the Herald owners want younger people because younger people are cheaper.”

This isn’t a young union. No one in the HTU is under 30; most are in their late 40s and 50s. But over the last year, some of those employees did what their former newspaper, with all its futurist bravado, still has not. They conjured a nimble, award-winning digital news outlet out of little more than pluck and spite.

“We thought if we were asking people to boycott the paper, we might as well give them something else to look at,” Krochak says.

ICYMI: Local Xpress journalists take gold in two categories at Atlantic Journalism Awardshttps://t.co/pHhXIB9iaa pic.twitter.com/yHUHULx3u5

— Local Xpress (@xpress_local) May 7, 2017

The first challenge of creating a strike paper was getting it off the ground. The Herald’s contract with its newsroom expired in November 2015, and as negotiations to replace it went south, reporters talked about establishing their own news site as a form of protest. But they didn’t start building one until after they went on strike the following January.

Maybe they should have been more prepared. McIlveen, who is on the Herald’s bargaining committee, says everyone expected negotiations would be hostile. But, she adds, in those early days, the union was putting its energy into a contract that could prevent a strike, rather than a website in the event one should happen. “We were prepared for the worst — well, expecting the worst, but prepared for something a lot better.”

As the strike began, some in the newsroom held back from the website, preferring to spend their time on the picket line. Not everyone in the union was a writer or photographer who could put their skills to use online — some were page editors or support staff. And amongst some of the content creators, says Frank Campbell, vice president of the HTU’s newsroom unit, there was fear about repercussions from management for competing with the company.

“The obvious concerns were the legality of it,” he says, adding that union lawyers looked at the idea and told reporters a strike paper was fine.

Working with a web developer, the Local Xpress team threw together a quick-and-dirty Squarespace site and drew up plans for how to run a digital-only newsroom: they’d chat over Slack; email each other photos to get around the website’s lack of an archive; get libel insurance to cover any controversial scoops; and plan a new workflow.

On January 30, about a week after the strike began, they had their first post up. Some spent the year throwing themselves into the outlet. Others spent more of their time on the picket line, often paying the Herald’s advertisers a visit to shame them out of doing business with their employer. And some folks did both.

But as reporters kept working on Local Xpress, it started to become clear they needed a better website.

So they relaunched in May with a bigger site, thanks to an agreement with Village Media, which runs a series of community news outlets throughout Ontario. Local Xpress now included obituaries, flyers, and wire copy. They also entered the battle for online ads, in an attempt to squeeze the Herald’s revenues.

The Halifax Typographical Union had, in setting up the website, gone from rank-and-file newsroom employees to revenue-soliciting media owners, using an initial contribution from the national union, ongoing donations, and the small number of ad sales to keep things chugging along.

“All the revenue, and it is NOT a staggering amount, goes back into the Xpress to pay for basic expenses for reporters and photographers and to the [union] local,” says Campbell in a text.

It’s been suggested that selling ads earlier and focusing on the outlet, instead of old-school picketing, would have been more strategic for Local Xpress: a way to hit the Herald in the pocketbook right as the strike began. Former Chronicle Herald reporter Mike Gorman — who, along with Frances Willick, was nominated for an Atlantic Journalism Award for his work with the Xpress — says “it would have been helpful” for ad sales “to have happened sooner.” But he adds, “We scrambled and we got a website up and we recognized there were some bugs we should try to improve, and we did. We’re not salespeople. We’re not website designers.” He and Willick now work for the CBC.

Building enthusiasm for the website during the seemingly endless strike — and keeping up energy for the boycott — has come with other challenges, especially in rural areas of the province. Media critics in Toronto can talk about the digital future all day long, but this is a place where 43 per cent of people lived in rural areas in 2011 — more than double the national rate. Many communities here still don’t have high-speed internet infrastructure. In some parts of the province, just downloading a PDF can be agonizing. If you don’t get a solid terrestrial radio signal and don’t see a broadsheet in the box at the end of your driveway, you don’t get the news. For some who would love to boycott the paper, their internet just isn’t good enough for the alternatives. From the Xpress’s beginnings, editor Pam Sword remembers being asked, “Can you do a print edition?”

Along with the regular issues of tech management and an aging news-consumer base, the Local Xpress team has also had to deal with brain drain. When the union first went on strike, 61 people were in the bargaining unit; now, there are 53.

With its awards in hand, Local Xpress now has its next battles to contend with. The Herald’s new Transcontinental acquisition will mean that the newspaper has plenty more professional content to fill its pages without resorting to strike-breaking labour.

The Chronicle Herald acquires TC Transcontinental’s media assets in Atlantic Canada, introduces SaltWire Network: https://t.co/LkWyjHtXaV pic.twitter.com/CpUYfzG3yP

— The Chronicle Herald (@chronicleherald) April 13, 2017

The Herald and the union have had several abortive attempts at negotiation. Last week, the Herald and the union met for another round of unsuccessful proposals that Campbell says ended in “mutual dispersal.”

One of the newspaper’s demands, Campbell says, is that Local Xpress hand over all its content. The reporters say that’s a deal breaker, and that while they do intend to shut down the Xpress after they get a deal, they want to keep up an archive of their work under the site’s original name.

If anything, though, Local Xpress can count the demand as a kind of victory: their digital experiment has clearly gotten under someone’s skin.

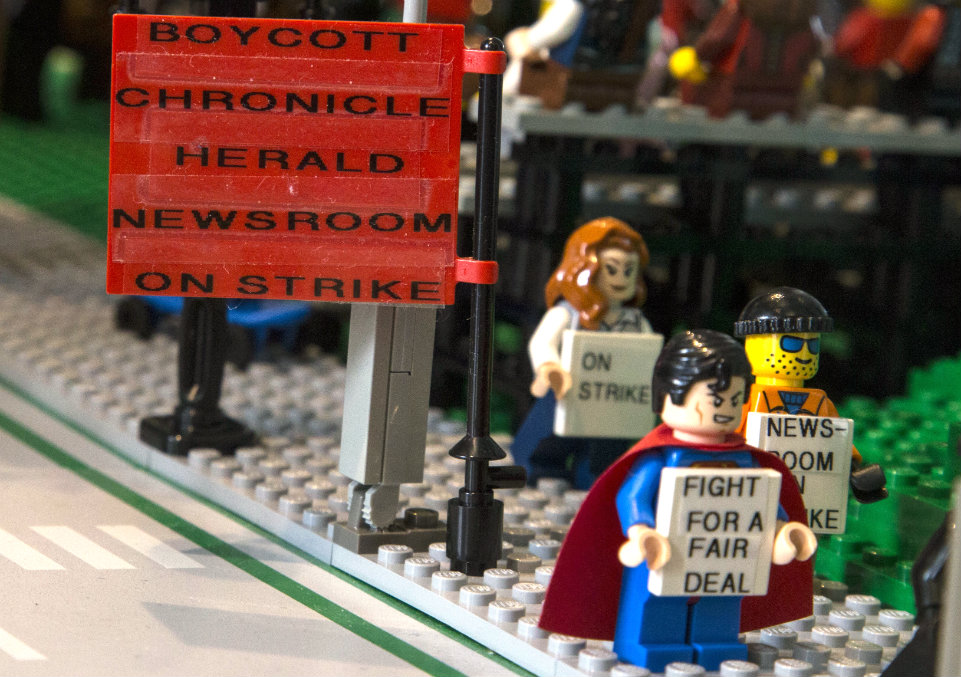

Photo of Gail Meagher’s Lego take on the Herald strike by the Xpress‘s Ryan Taplin.

Correction (5/11/2017, 1:50 p.m.): This story originally stated that the Chronicle Herald received a single Atlantic Journalism Award nomination and “left with just a glorified participation trophy.” In fact, it was nominated for three awards and won one, for editorial cartooning.